Rating: Must Have

Level: Easy (though helpful to have familiarity with liturgy); Long (400+), but each day is less than 10 pages

Summary

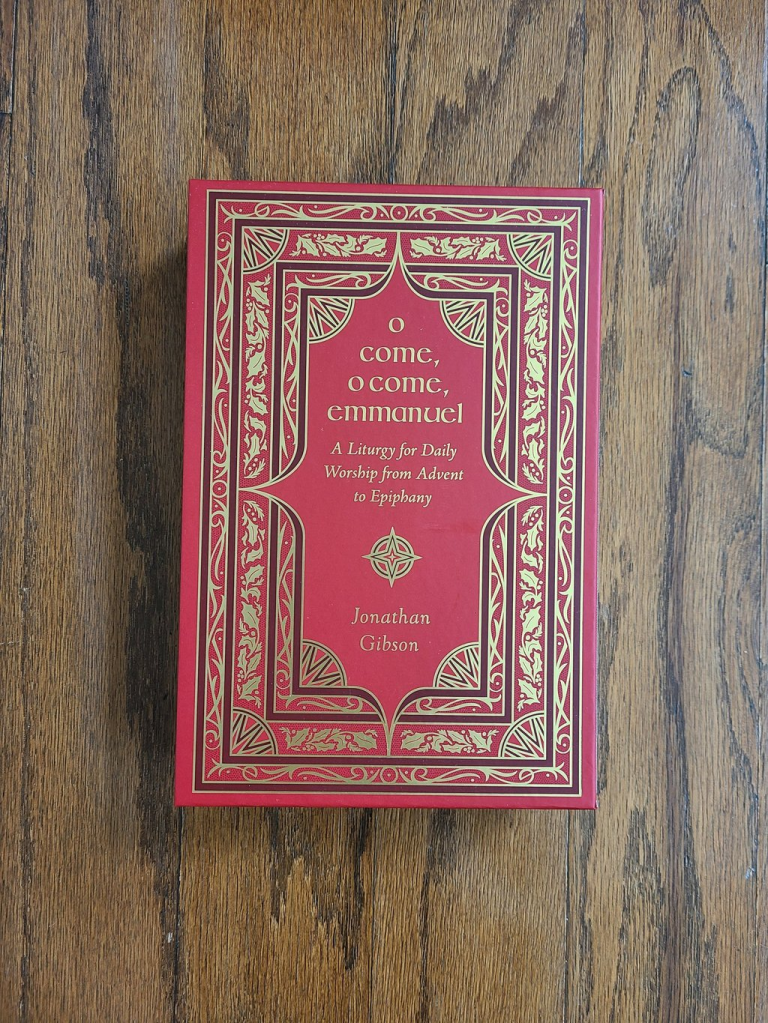

This is another outstanding book by Gibson and Crossway, similar to Be Thou My Vision, but this one being focused on Advent, Christmas, and ends on Epiphany. For those unfamiliar, that is January 6th, so to have a round number of 40 days, it may start before ‘official’ Advent. That was the case this year, Advent started yesterday (which is late in the chronological Calendar), and the book starts on November 28th, which was last Tuesday.

After a preface and acknowledgements, the books starts with an intro (titled Waiting For Jesus), where Gibson explains his reasons/hopes for this book. The following chapter is a very useful (especially if you aren’t used to Liturgy) ‘how-to’ on using the format, which includes: meditation, call to worship, adoration, reading the Law, confession of sin, assurance of pardon, creed, praise, catechism, prayer for illumination, scripture reading, praise, prayer of intercession (and then further petition/prayer), Lord’s Prayer, benediction, and finally a postlude (doxology).

There are also appendixes for tunes to various parts of the worship, Bible reading plan, and Author, Hymn, & Liturgy index.

My Thoughts

Honestly, if you attempt any personal or family worship this is a must have. I am a big fan of the structured (liturgical) worship, especially for family devotion. It really doesn’t make it easy to lead or do with your family or community. Really my only (minor) quibble with this is that with 16 parts, it might be just a little too long. However, if you are doing this with a family with young children or you find yourself short on time, there are always parts you can cut. That being said, some sections are only a line or a paragraph long; this shouldn’t take an hour or any extended time.

If you are unfamiliar with liturgy or structured daily worship this is an outstanding way to get into it. Unless you are from a pretty free-flowing Baptist/non-denom/mega-church background you will probably recognize parts (if not all) of these sections. If you are Anglican, you can see the clear influence of the BCP (which is probably the best book that exist for personal and family worship).

I know some people don’t like the repetitive nature of some parts of guides like these, saying and can be rote or unfeeling, but really that is up to you. If you don’t take it seriously, or just mindlessly repeat things, then yes, the downside is that it can be meaningless. However, the upsides are a daily reminder of how to worship God, what He has done for us, what so much of the church today and most have always believed and recited, and of course – scripture reading. This is more important than every in church life, especially if you do this as a family/community and use it to help shape and guide children in their beliefs. This is true of any structured worship, but I think is even more important for this time of year, when we are pulled away in so many directions, with so many competing interesting. As I said above, if you are looking for personal/family devotion/worship, this is a must have.

*I received a free copy of this book from Crossway, in exchange for an honest review.